Social distancing, flatten the curve, shelter in place, non-essential workers. These were terms that helped shape the investment world in 2020. A different set of terms is shaping 2021: Help wanted, shortages, on backorder, higher prices.

As the global economy re-opens in herky-jerky fashion from COVID-19 shutdowns, we’re sure it’s not news to you that the supply chains that underlie the production of many goods and the delivery of numerous services are significantly constrained by bottlenecks.

It’s also not news that the bottlenecks are causing shortages as the demand-side of the economy recovers more quickly than the supply-side. With demand outstripping supply, inflation is on the rise.

One aspect of the investment landscape has no lack of supply, however. In fact, in recent weeks, investor FUD (Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt) seems to have become increasingly plentiful.

Intensifying the FUD are potentially significant changes in “big picture” policies. Particularly with respect to:

Monetary policy. Will the rise in inflation prove “transitory” as the Federal Reserve (Fed) has been saying? Or are we witnessing the start of 1970s type of inflation?

Will the Fed abandon their long-standing, ultra-stimulative policy stance to fight inflation?

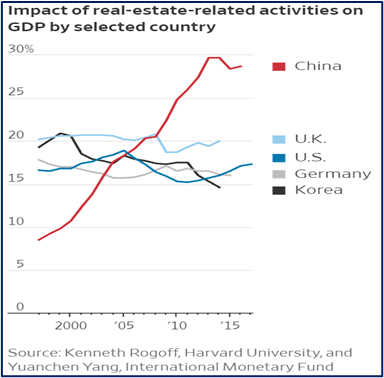

China’s massive policy change. Xi Jinping and his communist party have asserted control of the world’s second largest economy. Potential Xi rivals (business billionaires and millionaires) have been neutered (or worse). With an economy now being directed in top-down fashion by a modern Mao, what are the likely economic consequences for the world?

The state of the domestic Union. Despite a divided nation, U.S. politicians are determined to push “Big Government” to significantly larger proportions. What are the implications of massive new spending plans, raising taxes, and increasing government intervention in the U.S. economy?

Energy policies around the globe. Power grid instability and soaring prices of energy products are hitting the U.K. and much of Europe in what is being called a perfect storm. Increased reliance on solar and wind for power has made electric grids vulnerable after an extended period of calm and cloudy weather. This has increased dependence on natural gas which is in short supply in the Eurozone and the U.K. Vladimir Putin is delighted to help fill the void with his country’s gas and pipelines (at very dear prices, of course).

Following is our investment perspective on these and related issues.

Pencils

Intricate global supply chains underlying commerce are not a recent development.

Consider the ever-so mundane pencil.

Even in our increasingly high-tech world, each year roughly 2 billion low-tech pencils are sold in the U.S. and 14 billion are sold worldwide.

Way back in 1958, Leonard Read—a founder of the Foundation for Economic Education—wrote a short essay entitled I, Pencil.

The essay traces the global supply chain underlying the production of pencils—the wood, the lead (graphite), the finishing lacquer, the materials of the rubber-like eraser, and the ferrule which holds the eraser on the pencil. And recall that Read was writing about this in 1958, well before globalization really took off.

More important, however, is the essay’s argument that even in the case of a product as seemingly simple as a pencil, its production is an amazingly complex process.

So complex, in fact, Read asserts that no single individual has knowledge sufficient to construct a pencil from scratch. No one person knows how to grow, harvest and mill the timber, mine and mold graphite, smelt the materials that comprise the ferrule and eraser, or brew the lacquer—all of which are part of the processes for making a pencil that you can buy online for about a dime.

The production process of a pencil is dynamic in nature. It’s constantly being improved upon and adapted for changing circumstances related to changing consumer preferences, the sales climate, competition, and new regulations (the last U.S. graphite mine, for example, ceased operations in the U.S. during the 1990s). The coordination, ingenuity, efficiency and timing behind the production and sale of a pencil resembles something close to magic.

And that’s just for the simple pencil. Repeat a similar process across all the goods (and services), across the economy, and large-scale magic happens!

Supply chain troubles unlike anything since the end of World War II

The magic of market-based commerce typically works so well that it’s easy to take for granted.

Until COVID-19 shutdowns that is. The disruption to supply chains from the lockdowns is a very “big deal”. As the pencil discussion suggests, supply chains for even seemingly simple goods are complex. They may have been abruptly stopped by the shutdowns, but getting the magic restarted takes time.

The economy has not experienced anything like this since the end of World War II.

What can be gleaned from this earlier period? Let’s take a quick look back and see.

After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 and the declaration of war against the U.S. a few days later by the Nazis, our nation’s economy was about to undergo a massive pivot. Production within the economy would be largely redirected from private sector goods towards military equipment.

To focus and speed the pivot, in January of 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt established the War Production Board (WPB). From 1942-45 the U.S. economy was largely directed by the WPB.

Just how significant was the shift away from the production of consumer goods? Reports indicate that no civilian cars, commercial trucks, or auto parts were produced from early 1942 until after the War’s end in 1945. More broadly, consumer goods of all kinds were in short supply as price controls and strict rationing were the law of the land during those years.

After the War ended in 1945, the WPB ceded control of the economy back towards the private sector. Wage and price controls were lifted.

The pivot back to the production of private sector goods was a process that took a considerable amount of time to unfold.

The adaptation process was likely slowed by widespread FUD about the U.S. economy’s prospects. With war production over, many were worried that the massive unemployment and economic hardships of the 1930’s Great Depression were destined to return.

A slump did occur in the years immediately following the end of the War. But unemployment did not skyrocket back up anywhere close to Great Depression levels. And the economy soon began to grow again.

Prices did surge higher, however, as pent-up demand and spending overwhelmed the cautious, slow ramp up in private sector goods production. Over the five years following the War’s end, inflation averaged more than 6% with a large rise (18% in 1946) as wage and price controls were lifted immediately after the War, and a year where prices declined (an estimated 2% decline in 1949).1

As the 1950s unfolded, the economy’s “supply side” adapted to private sector goods production and market-based commerce was busy performing its magic. The rate of inflation eased and averaged less than 2% over the course of the decade.

How did stock prices fair during this period? After more than doubling in value during the war years 1942-45, stock prices suffered a relatively modest setback (-8%) in 1946 as the economic uncertainty noted earlier set in after the War’s end. From then on stock prices followed corporate earnings growth which powered higher throughout the decade of the 1950s.

Dynamism, adaptability = economic resiliency

We have noted on prior occasions that two of the significantly underappreciated aspects of the U.S. economy are its dynamism and adaptability. Each day in I, Pencil fashion, millions of minds are busy thinking of ways to do things better, easier, safer, and using fewer physical resources.

More exciting still, fertile minds are being provided with emerging technology tools that are opening new avenues in adaptation and problem solving. COVID-19 vaccines are high-profile examples of promising medical breakthroughs that biotech, life sciences and genomics may well deliver over the next few years.

It will take time, but we believe the odds favor months and not the years it took after World War II for dynamism and adaptability to alleviate many of the supply chain disruptions created by the COVID-19 shutdowns.

In terms of inflationary pressures associated with shortages, there’s an old saying that higher prices are often the cure for higher prices.

One can see some examples of this dynamic already at work. Last year’s shelter-in-place mandates triggered a boom in home fitness equipment. Indoor cycling company Peloton struggled to meet surging demand for its products and related services. Delivery times for Peloton bikes grew from a couple of weeks to many months.

Peloton has since expanded its production capabilities via an acquisition. Delivery times are back near, or below, pre-pandemic levels. And, by the way, it has been compelled by intense competition to drop the price of its premier bike below pre-COVID-19 levels.

Today’s economy appears much less inflation-prone than was the economy of the 1970s

While supply chain price pressures might ease in the coming months, what about the large growth in the traditional money supply figures that are the result of COVID-19 relief measures?

Adherents to the quantity of money theory (generally known as “monetarists”) believe inflation is solely a monetary phenomenon. In other words, inflation is triggered when governments print (create) “too much” money.

We believe context matters in the money creation-inflation relationship. The underlying structure of an economy can either amplify or dampen monetary traction.2

The demographic and the technology backdrop underlying today’s economy is significantly different than the structure of the 1970s economy. We believe these factors have reduced how much traction monetary policy gets within the traditional money creation-inflation linkage.

Much of the money created in the wake of the pandemic sits within the banking system as “non-borrowed reserves”. By contrast, in the 1970s, bank reserves didn’t sit around very long as loan appetite by the coming-of-age baby boomers was robust.

Some of us boomers recall becoming first time homeowners by taking out mortgages with interest rates well above 10%. Today, economists fret that new home sales will stall if mortgage rates exceed 3%!

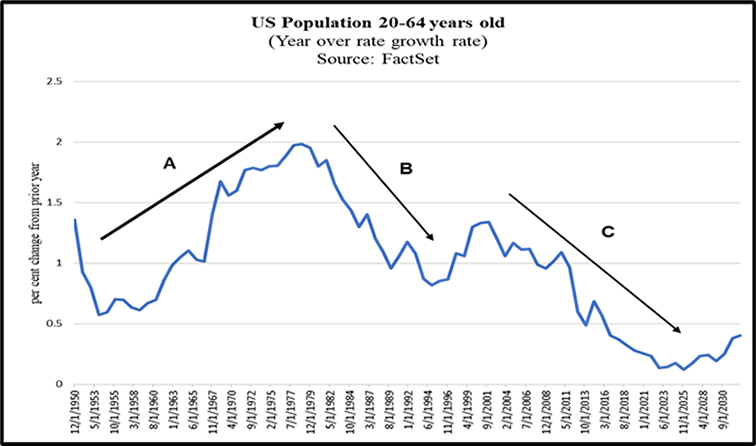

To see how the demographics backdrop underlying the economy has changed over time, please see Chart 2.

The ‘A’ arrow in Chart 2 reflects the coming-of-age of the baby boomers as “key spenders” driving consumption within the economy. The baby boom delivered a persistent demand shock to the supply side of the economy during the 1970s. Back then, the supply side of the economy was constantly strained to keep up with strong demand.

Arrows ‘B’ and ‘C’ in Chart 2 reflect the significantly slower growth that’s occurred in “key spenders” within the generations following the baby boom.

The overall population is still growing (although slowly), but the rate of growth in demand for goods, services, and loans is significantly less than was the case with the baby boom. Meanwhile, the supply side has both expanded capacity and become more efficient in I, Pencil fashion, at meeting demand.

The emergence of the digital economy has also likely reduced monetary traction within the economy relative to the inflationary 1970s. Bits and bytes scale rapidly without needing lots of loans or physical assets.

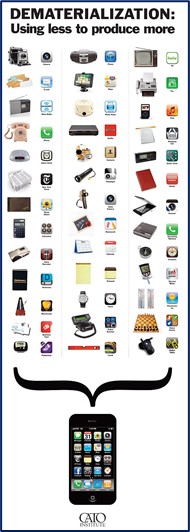

As we’ve noted on previous occasions, economists are calling the tangible asset light trend “dematerialization”.

Economic growth without commensurate growth in physical resources is a recent phenomenon, and we believe not widely recognized nor fully appreciated.

Dematerialization is probably most easily communicated by the nearby graphic which shows all the physical goods the smart phone has replaced.

What does all this likely mean for Fed policy?

In recent weeks the Fed has been preparing investors for an incremental shift towards a less stimulative policy tilt. This shouldn’t be a shocker. The emergency policy stance adopted in the heat of the COVID-19 shutdowns is not likely needed as re-openings continue to unfold.

Inflation will likely remain above its longer-term trend until COVID-19 related supply chain pressures are alleviated. But against the backdrop of an economy that does not appear structurally inflation prone, odds are the Fed will have the luxury of executing policy changes in an incremental manner.

What if the economy proves more inflation prone than we have outlined and inflation persists over a multi-year time frame? What would be the associated investment implications?

- Bonds: The bond market would take it on the chin if higher rates of inflation prove to be a long-lasting problem. Bond prices would erode as yields would be pressured higher to compensate investors for higher inflation.From a portfolio perspective, our analysis suggests bonds generally already have an unfavorable risk/reward profile even if inflation remains at the Fed’s target rate of 2%.

Therefore, the short-term bonds that populate our bond investments within portfolios are already “defensive” in structure and possess very modest interest rate risk exposure. Higher bond yields would be viewed as a potential opportunity.

- Stocks: Over time, we believe one of the most enduring investing relationships is the link between a stock price and the earnings power of the underlying business. Stock prices follow the earnings prospects of a business.The role of the stock market is to allocate capital to its “highest and best uses”. This simply means that, over time, a business that sustains strong earnings growth becomes worth more. It attracts capital. The stock of a struggling company, by contrast, typically suffers as an investment as capital shifts elsewhere.

Companies compete for customers. Strong earnings growth is the result of providing goods and services that please customers by making their lives better and/or easier by helping solve some customer problem(s).

These aspects endure whether a low or high inflation environment exists. In the latter case, our research of past episodes of escalating rates of inflation, suggests that the ownership of businesses that consistently generate earnings growth above the rate of inflation proved to be very rewarding investments.

It’s also important to note that the businesses we own include many that provide productivity enhancing tools to other businesses. These tools are in many cases, as essential to their customers’ businesses as electricity or running water.

Rising inflation puts additional burdens on firms to run as efficiently and productively as possible to counter rising labor and other input costs. We believe demand for productivity tools would remain durable in such an environment and help power the earnings growth of our portfolio companies.

Furthermore, if the Fed had to adopt restrictive policy measures, economic growth would slow as would the growth in sales and earnings of many businesses. Investors in stocks of companies that would be able to sustain superior earnings growth would likely be well rewarded in that environment.

Speaking of slow growth…

Increased economic intervention by governments is likely to slow economic growth

We believe the tax hikes, spending plans, and increased regulations being debated in Washington D.C. will prove to be wet blankets on productivity and economic growth.

This is not offered as a political statement, but as a statement about resource allocation.

Taking resources from the more productive private sector where the I, Pencil magic of market-based commerce occurs, and having them directed instead in “top down” fashion by the less efficient government sector, is not helpful from a productivity or economic growth standpoint. And productivity growth is what drives the standard of living higher over time.

Recall that the main message of I, Pencil is that know-how is about managing important details. But even simple products involve astounding detail complexity. If making a pencil is hard, how about a remaking of a power grid? The U.K. power instability situation reflects that skipping over, or wishing away, important details is a recipe for serious unintended consequences.

As for Xi asserting control over the Chinese economy, good luck with that. Replacing creative innovators/entrepreneurs with party-loyal bureaucrats is not conducive to economic growth.

If a pencil is complex, and a power grid is even more complex, what about an entire economy, or societies? The Neil Irwin quote below suggests an answer. More hubris needed from policymakers?…YES PLEASE.

Investors should prepare for a backdrop of generally slow economic growth and financial market volatility. The stocks of businesses that can sustain superior growth are the investment way forward. Enduring volatility along the way will be worth it!

“Macroeconomics (assessing the economy from the top down), despite the thousands of highly intelligent people over centuries who have tried to figure it out, remains, to an uncomfortable degree, a black box. The ways that millions of people bounce off one another — buying and selling, lending and borrowing, intersecting with governments and central banks and businesses and everything else around us — amount to a system so complex that no human fully comprehends it.”

–Neil Irwin, Senior Economics Correspondent, The New York Times

October 1, 2021

Sources & Notes

1 Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation Yearbook by Ibbotson Associates

2 For more on this line of thought see The Great Wave, Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History by David Hackett Fischer, Copyright 1996, Oxford University Press, and The Fed and the Great Virus Crisis, by Ed Yardeni and Melissa Tagg, Copyright 2021, YRI Press, or see the work of Economist/Demographer Richard Hokenson.